The recent death of Ted Kennedy prompted me to pick up some of the Kennedy books I have lying around the house and I have just re-read a book about JFK that shook my world a couple of years ago. It illuminates a story about a beloved president that was never told prior to this book being published. It’s been hidden from history, or at least overlooked by every biography ever written about JFK.

John F. Kennedy is one of the most studied and written-about presidents of the 20th century. Aside from the remaining mysteries surrounding his assassination, there is little that is unknown about the life of the thirty-fifth president of the United States. Or so we thought.

In Jack and Lem, published by Avalon, writer David Pitts sets about uncovering the story of Jack Kennedy and his closest and dearest friend in the world for 30 years, Lem Billings — a gay man.

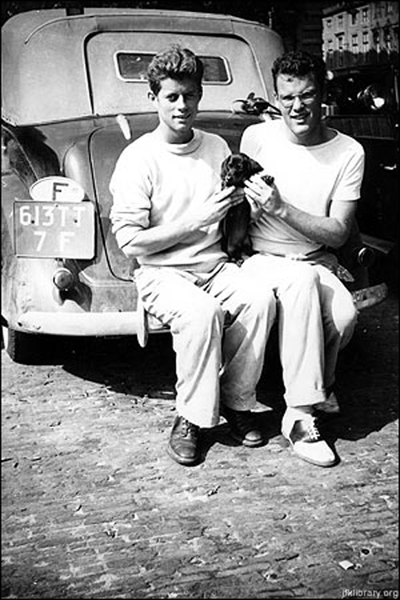

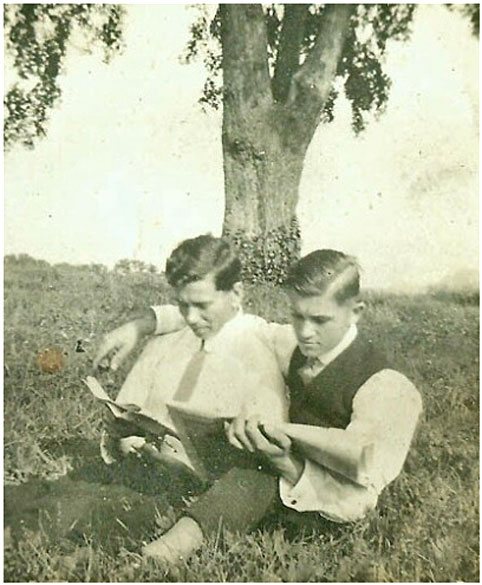

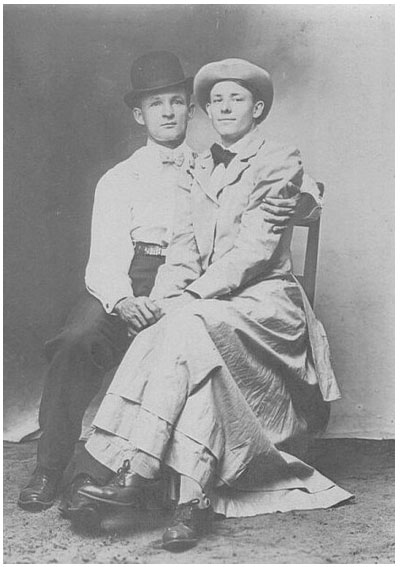

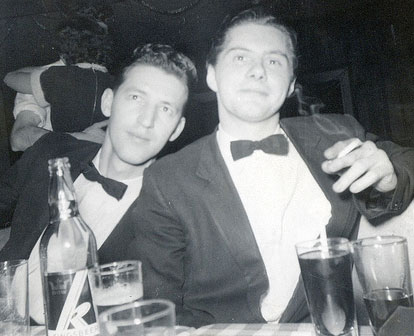

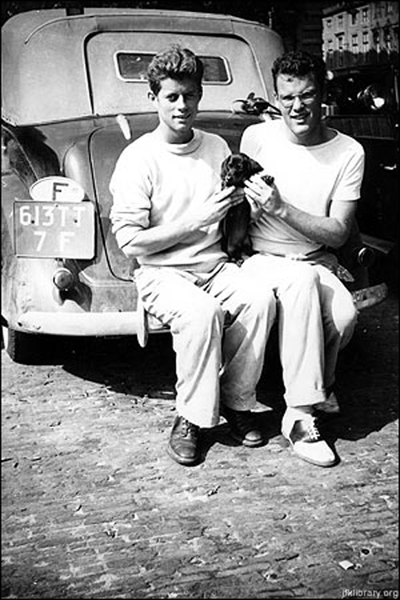

Jack and Lem met while at prep school in the 1930s and from that point on were inseparable until the day Jack Kennedy was killed. Pitts worked for two years to persuade Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. to grant him research access to documents that have been locked away for decades, including letters between the two friends, recorded phone calls, and even an 800+ page transcription of an oral history that Lem Billings gave after the death of the president. Pitts also combed through hundreds of photographs never seen by the public, many of which he was allowed to publish in the book, and interviewed anyone and everyone he could who knew Jack and Lem so he could tell, as accurately as possible, the story of a president and his gay best friend.

This well-told account paints a tender, moving portrait of what the author calls “an extraordinary friendship,” the details of which enchant and move the reader. Anecdotes about Lem having his own room in the White House, how Jackie Kennedy dealt with having a third person in her marriage, and other bits of lost history aren’t taught in any school text books, but they are told in this book — for the first time.

I interviewed David Pitts about Jack and Lem when this book came out. It’s important to me that this story not be forgotten and now, as we say goodbye to to Ted Kennedy and Eunice Kennedy and regard the legacy of Camelot, this seems like a good time to share it again.

Kenneth Hill: How would you characterize the friendship between JFK and Lem Billings?

David Pitts: The way I would characterize it is that is was a very close, deep, friendship across sexual orientation lines.

KH: How did you first learn about it?

DP: I first learned about the friendship from reading JFK books. I am such a Kennedy fan that I read most of the new JFK books that came out over the years. Lem was mentioned in some, but there was always very little information about him — usually one or two pages — and I just became curious about, well, who exactly is this guy? And that’s how this book that I wrote came about.

KH: How did you find out who he was?

DP: The first thing I did was to look at all the books again to see what had been said about him, which, as I said, was very little. Then I then compiled a list of people to call, people to interview that I thought might know more. I also set about trying to track down documents in various institutions — most notably the John F. Kennedy Library and the Massachusetts Historical Society. And on the latter, I hit a big brick wall early on in the project, which is why it took so long. Most of the documents, including, very significantly, an 815-page oral history done by Lem, were closed to writers and authors. Many of the quotes of Lem in the book are from that document. And it was closed at the Kennedy Library and required the permission of Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. to access it, and he didn’t give it to me for a long, long time.

KH: How long?

DP: I would say about two years. Two years into the project before Bobby, I guess, got tired of me pestering him.

KH: Why do you think there was resistance?

DP: I don’t know. I’ve been asked that quite a few times — usually I’m asked why he in fact GAVE me the documents — but I really don’t know. I can’t answer that. He didn’t agree to an interview, I wanted an interview, as well, but he did give me the documents which in a sense were more valuable. But when he decided to give me the materials, he gave me everything without restriction, including the ability to copy them as well as quote from them.

KH: Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and Lem were close when Bobby was a young man, right?

DP: Yes, that’s how Bobby ended up with control to most of the materials. Lem knew Bobby from when he was very young, of course, Lem being an intimate of the Kennedys, and when Lem died in 1981 his belongings passed into the possession of Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. Some of his things went into the possession of his neice, Sally Carpenter.

KH: Lem was a friend of the Kennedy family during the time that JFK was alive, and also after he was assassinated. Did you have any sense that this was a story that they didn’t necessarily want to have told?

DP: No, I can’t really say that. I mean, none of them agreed to an interview, although Eunice Kennedy Shriver who knew Lem very well came very close and then she became ill. So if I was to guess, and this is purely a guess, I think Bobby Kennedy and the other Kennedys knew this story was going to come out sooner or later. They probably checked me out — I’m sure they did — and were more willing to trust someone with a liberal political bent than some conservative writer who might try to use it in a sensational way. That would be my guess.

I did talk to a friend of Bobby Kennedy when I was trying to get these materials and when I was trying to talk to Bobby, by the name of Blake Fleetwood, who’s a blogger himself on the Huffington Post. He also knew Lem. He told me that the Kennedys have been burned so many times now in these conservative times by writers, they just are very very suspicious of writers, period. It’s not about this story in particular, it’s about any story. And so I think if you take him at his word, part of the reason must be just suspicion of journalists these days.

KH: You said that this was the story of a friendship that crossed sexual orientation lines, which I think is really an interesting element of it, but talk a little bit about the depth of this friendship. The fact that it started when they were very young and, from what I read in the book, they were basically inseparable for the rest of their lives except when circumstances had them in distant cities. Read More »

Tagged: biography, David Pitts, Edward Kennedy, Eunice Kennedy, gay, Jack and Lem, Jackie Kennedy, John F. Kennedy